|

Oldline Protestantism:

Pockets of Vitality Within a Continuing Stream of Decline

David A. Roozen

Hartford Institute for Religion Research Working Paper 1104.1

Hartford Seminary, 2004

Introduction

Forty years ago a group of researchers gathered to plan the first set of empirical studies of mainline Protestant membership growth and decline since Dean Kelly’s attention getting, Why Conservative Churches are Growing[1] and the, at the time, less visible launch of the Fuller Seminary-centered, Church Growth Movement.[2] The eventual publication of the research, Understanding Church Growth and Decline,[3] pinpointed the mainline’s membership dip into the red as occurring in 1965 and touted two major findings of special note here. First that the mainline declines were primarily due to social demographic changes, the two most prominent being the dramatic value changes being carried into young adulthood by the baby boom generation and population shifts out of geographic areas of traditional mainline strength. Second, that a combination of the social changes and membership declines were intimately related to a crisis of identity within the mainline. One topic not addressed in the research was the likely future direction of the declines; and one nuance not articulated was the possibility that the reason the external factors of social change appeared as the drivers of decline was the mainline’s inability to adapt its internal style, program and message to the changing world around it. The purpose of this article is to address these two issues. What has been the trend in formerly-mainline-now-oldline Protestant membership and vitality since the 1970s? What does the data currently show us about the dynamics of oldline growth and vitality, especially about the internal, adaptive capacity of those organizations in which Protestants hold membership – specially, congregations.

One of the more helpful consequences of all the attention given in the late 1970s to the original research and commentary on the oldline membership declines was a questioning of whether or not membership trends were an appropriate gauge of the/a church’s faithfulness. Although the debates were often clouded in obtuse abstractions and subtlety overlaid with the typical, academic deconstructive strategy of caricaturing one’s opponent, two issues dominated. One was whether evangelism (pro-membership growth) or social justice (highlighting the costliness of discipleship) was the primary purpose of the church. A second was whether or not God would provide the blessing of growth to faithful congregations. The pro-growth position within the latter was that while membership growth per se was not the primary purpose of the church, God surely intended for faithful congregations to grow. Two generations (and two generations of continual membership declines) later the debates continue with two major differences. One is that they seem less intense and less direct, perhaps because after forty years of losses few mainliners are against recruitment and/or development efforts that can be, correctly or incorrectly, passed off as evangelism and social justice has lost its edge as denominational identities have become more diffuse and contested. Perhaps more importantly, the last decade or so has witnessed an increasing emphasis on multi-dimensional notions of congregational vitality, with an especially strong surge of interest and prominence being given to “spiritual vitality.”

Hopefully other articles in this collection will vigorously and dialogically explore the variety of possible normative definitions of vitality, including my own personal preference for the affinity between multi-dimensional approaches and post-modernity. The latter notwithstanding, the major thrust of my analysis will focus on membership growth for three reasons. Most importantly and comforting, all empirical studies including multi-dimensional measures of congregational vitality of which I am aware show that membership growth is significantly related to other possible indicators of vitality. That is, congregations that show high levels of mission outreach, spiritual vitality, financial health, lay involvement, etc also tend to be growing. More pragmatically, membership growth is the most concrete and statically robust measure of vitality available in the largest national sample survey of congregations (over seven times larger than the next largest) available for multivariate analysis. Finally, there is a much more substantial body of social scientifically informed literature on membership growth than for any other of the currently debated measures of congregational vitality.

Choosing a measure of congregational vitality is a debatable enough decision in itself, but it begs an equally vexing and even more foundational question. When dealing with theological, spiritual or religious matters, why bother with measurement and human statistics at all? It is a question that has haunted religious research since its outset:[4] and as Smilie has reminded church growth researchers, Barth presented as far back as 1948 a particularly clear and passionate argument against confusing membership trends with questions of faithfulness. It is beyond this paper to argue the case for the value, much less necessity, of using human agency in general, much less a social scientifically informed rationality in particular, as a vehicle for God’s purposes.[5] Therefore let it suffice to note but two major dimensions of such an argument. One would build on the simple fact that the dismissal of human agency occupies an extremely minimal space in both the long history and contemporary currency of Protestant theology, especially that of liberal Protestant theology. A second, more defensively deconstructionist tact, and one more specifically in regard to the statistical measurement of changes in growth, would use Smilie’s rejoinder to Barth as a point of departure: “Some observers, unable to relieve themselves of “all quantitative thinking,” might observe that Barthians in Europe have succeeded in lowering membership and participation without necessarily lifting the quality of life of the body of Christ.”[6]

So on to our empirical case! With the exception of one brief, introductory dip into denominational membership figures reported by the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches, the data for my analysis comes from the recent (2000), Faith Communities Today (FACT) national, interfaith survey of 14,301 congregations in the United States. FACT2000 was a cooperative effort among agencies and organizations representing 41 denominations and faith groups – from Southern Baptist to Bahai, Methodist to Muslim to Mormon, Assemblies of God to Unitarian Universalist, Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Jew, and all the usual oldline Protestant players. The groups worked together to develop a common, key informant questionnaire. Groups then adapted wordings to their respective traditions and conducted their own survey, typically mailed during 2000 to a stratified random sample of a group’s congregations. Return rates averaged over 50% with independent congregations proving their independence with the lowest rate of return and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints demonstrating one of the virtues of hierarchy with a 98% return rate. Data from the total of 14,301 returns from the various group samples were sent to the Hartford Seminary Institute for Religion Research for aggregation. Zip code level census data was added to each congregational case and the cases in the aggregated dataset weighted to provide proportionate representation of each denomination and faith group. The survey was funded by the Lilly Endowment, with matching funding from the participant groups. More detailed information about participants and methodology, as well as an electronic copy of the original FACT report and core questionnaire can be found on the FACT website: www.fact.hartsem.edu.

Hope or Reality

For those who value oldline Protestantism, it is undoubtedly refreshing to hear all the hints and rumors of vitality that have been swirling around for the last decade or so. Some proponents, including contributors to this volume, have even suggested that oldline Protestantism is currently the most vital stream of Christianity. With all due respect for the strength of the latter’s imagination and depth of hope, and while there certainly are identifiable pockets and sources of oldline vitality, any claim to the oldline’s dominance of the religious vitality market, at least in the United States, unfortunately flies in the face of the empirical reality. In their editing of the 1993 follow-up to Understanding Church Growth and Decline, Roozen and Hadaway charted out the membership trends for every denomination with consistently reliable data for 1950 through 1990 in the Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches.[7] Among others, this included eight denominations that would be considered oldline Protestant and 15 that would be considered conservative Protestant. Figures 1 and 2, below, update the Roozen and Hadaway figures to 2000.[8]

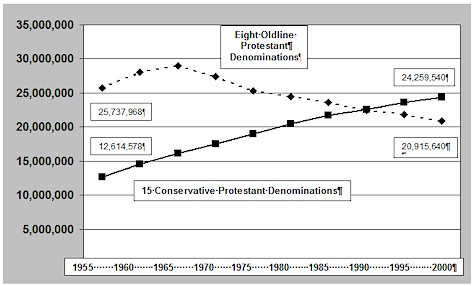

FIGURE 1: Oldline and Conservative Protestant

Trends in Membership: 1955 - 2000

Figure 1 makes one point clear and suggests another of note. What is clear is that the mainline-now-oldline membership decline that began in the mid-1960s continues to the present, and that this contrasts sharply with continual conservative growth. What is suggested, although not decisively shown in the figure is that conservative Protestants now outnumber mainline Protestants.

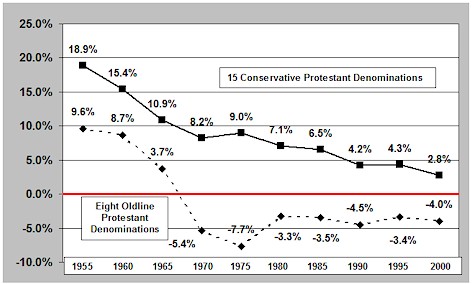

Figure 2 presents the same data, except charting the rate of growth/decline rather than the actual number of members. For those with a desire for an oldline spin, it presents a somewhat more optimistic assessment than Figure 1. It shows, for example, that the oldline rate of decline is currently only about half of what it was at its worst in the mid-1970s. It also shows that during this very same time that the oldline decline was easing, conservative grow progressively slowed such that the conservative advantage in 2000 was only about a third of what it was in the mid-1970s. Unfortunately for the vitality of the oldline cause, the closing of this gap over the last 20 years has come totally from the decreasing strength of conservative Protestant denominations, rather than from any overall gain in strength in the oldline. Indeed, it has to be noted that the rate of numerical membership decline within oldline Protestantism has held steady at just under 1% a year for the past 20 years.

FIGURE 2: Percentage Change in Membership

Over Previous Five Years

One could appropriately object that, given conservative Protestantism’s strong theological and practical investment in evangelism, the use of membership growth as one’s sole measure of vitality in a comparison with oldline Protestantism stacks the deck in favor of the conservative. Figure 3 suggests that such an objection is partially correct. It uses data from FACT2000 to compare oldline and conservative on a rather broad array of conceivable measures of vitality.[9] Most importantly for oldline advocates, it does show that for measures of ecumenical and interfaith involvement, and for social outreach and social justice, and for the physical condition of a congregation’s property, the oldline outscores its conservative counterparts. Nevertheless, the figure also shows that on balance, indeed by a margin of more than 2 to 1, conservative Protestantism leads the way in a much more extensive and wider set of measures than does oldline Protestantism, including for example, spiritual vitality, inspirational worship, purposefulness, welcoming change, extent of congregational programming and financial health. Additionally, if one were to add in the FACT2000 data for congregations in the Historically Black denominations, oldline Protestantism loses its lead in social outreach and social justice. Then if we add in the FACT2000 Jewish congregations, oldline Protestantism loses its lead in the area of ecumenical/interfaith relations. The net result: oldline Protestantism only leads the Judeo-Christian tradition in the United States in the physical condition of its buildings.

Figure 3: Comparative Strength of Oldline and Conservation

Protestant Congregations* |

|

Oldline Protestant |

Conservative Protestant |

Considerably

Stronger** |

Ecumenical Worship

Interfaith Worship

Ecumenical Social Ministry

Interfaith Social Ministry

|

Clear Sense of Mission & Purpose

Deepen Members’ Relationship With God

Expressing Denomination Heritage

Moral beacon in the Community

Excitement about Future

Emphasis on:

Personal Spiritual Practices

Family devotions

Keeping the Sabbath

Membership growth |

Moderately

Stronger*** |

Emphasis on Social Justice

Number of Social Outreach

Programs

Physical Condition

Of Buildings

|

Inspirational Worship

Sense of Spiritual Vitality

Close-Knit Family Feeling

Trying to Increase Racial/Ethnic Diversity

Welcome’s Innovation and Change

Dealing Openly with Conflict

Assimilating New Members

Number of Member Oriented Programs

Financial Health |

No Meaningful Difference**** |

Well Organized

Amount of Serious Conflict |

*Based on the Faith Communities Today 2000 national survey of 14,301 congregations: fact.hartsem.edu

** More than a 10 percentage point difference in congregations falling into the positive extreme response category

*** A 2 to 10 percentage point difference in congregations falling into the positive extreme response category

**** Less than 2 percentage point difference |

Fortunately, the rumors of vitality in oldline Protestantism are not totally unfounded and pockets of strength are clearly evident.[10] One finds in FACT2000, for example, that 45% of oldline Protestant congregations report membership growth between 1995 and the year of the survey. Among other things, this means we have ample numbers of such congregations in the FACT2000 dataset for an in depth exploration of the sources of growth, the task to which we now turn.

Oldline Sources of Adaptive Vitality and Growth: The Theory

Religion and the social sciences merged just before the turn of the twentieth century, in the United States, as the Social Gospel movement emerged in response to waves of economically marginalized immigration that washed across established urban neighborhoods in costal, Northeastern cities. By the time this initial flourishing of religious research had differentiated itself and reached its zenith with the publication of The Protestant Church as a Social Institution in 1935, it had established what would be the common wisdom of church growth studies for the next fifty years: As goes the neighborhood, so goes the church.[11] Kelley’s presumption that strictness was the reason why conservative churches were growing and liberal churches were declining was the only major, social scientifically argued alternative to the demographic or contextual captivity of church growth studies through the 1980s.[12] Next to strictness the only other internally focused explanation for oldline declines that gained significant currency at the time was the divisive support for social justice voiced by many oldline pastors and denominational leaders. Neither found significant empirical support in Understanding Church Growth and Decline, the latter highlighting the primacy of neighborhood population changes as the leading predictor of congregational growth.[13] The affinity of demographic change explanations for mainline decline with the homogeneity principle of the Fuller Church Growth Movement sweeping conservative Protestantism at the time, kept church eyes focused outward.[14]

The rumor or hope that congregations were not totally captive to their context received new energy in the late 1980s as a group of economists interjected supply side, rational choice arguments into the sociology of religion. The foundational presupposition of this approach is that the more individuals sacrifice on behalf of their religion, the more benefits they receive, hence the applicability of rational choice models. One implication of this for present purposes is that churches are in control of how much sacrifice they demand of members, hence the “supply” side emphasis.[15]

If this feels like Kelley’s “strictness” thesis being recast in economic terms, it is; and that is exactly how the new socio-religious economists presented it. Only instead of Kelley’s appeal to the sociology of knowledge and plausibility structures, the new socio-religious economists drew on the extensive economic literature on free riders. Truly rational actors will not pay for something when they can get it for free. Free riding churchgoers take worship and other religious goods without further investment of time or talents. Strict religion, accordingly, strengthens a church for two reasons. Sacrifice increases the individual commitment of those who stay and drives away those unwilling to contribute of congregational life.

Applying this argument on a more societal scale, the new socio-religious economists provided a wonderfully parsimonious answer to one of the more perplexing problems of classical sociology of religion. Why has not religion withered away in arguably the most secularized country in the developed world, namely the United States? Two primary reasons. First, the separation of church and state allows for a free-market religious economy. Second, because of this and while it is true that established religions tend to get less strict over time, new religious groups appear that present new and contextually adaptive forms of strict religion.[16]

Innovation in religious product is what has kept religion vital in the United States, and this innovation arises through entrepreneurial new firms (movements or denominations). The good news in this for religious establishments is that it recognizes the reality and centrality of a continuing “demand” for religion and of innovation in a vital religious marketplace. The bad news is that it seems to preclude the possibility that significant innovation can come from within established religions to produce the religious product that the customers want to buy.

Was there nothing identifiable in the empirical research, beyond the testimony of a few seemingly idiosyncratically successful pastors, that oldline Protestant congregations could do to stem membership decline? With the help of a new emphasis on congregational surveys, in contrast to the limitations of yearbook statistics and extrapolations from individual surveys, the 1990s seemingly ushered in a hot pursuit of this question among religious researchers. One of the first compilations of such research, Church and Denominational Growth, reached two noteworthy conclusions in this regard. First, “Growing [oldline] churches emphasize outreach and (or) evangelism . . . [T]he key is an ‘outward orientation.’ Churches that are primarily concerned with their own needs are unlikely to grow.”[17] Second, at least for oldline congregations, the studies concluded that: “There is no clear relationship between strictness at the local congregational level and church growth.”[18] And indeed, in contrast to Kelley’s conservative strictness, the studies showed that if anything, again among oldline congregations, there was a small association between growth and liberalism.

But it wasn’t until almost a decade later and the FACT2000 national survey of American congregations that the empirical research really began to get interesting for those looking for an adaptive capacity within oldline congregations. Two initial explorations of this terrain using FACT2000 followed from hints from research focused on slightly different issues. One focused on the apparent important of new forms of, especially, contemporary worship within the currently most vibrant streams of conservative Protestantism.[19] The other took a look at seeming preference of baby boomers for spiritual practices.[20]

In my 2001 H. Paul Douglass address to the Religious Research Association I used a comparison of the ground breaking work in congregational studies from Douglass’ Institute for Social and Religious Research with the data from FACT2000 to ask how what we know about congregational vitality may have changed over the course of three quarters of a century.[21] Of particular interest was whether the reality or our understanding of the dynamics of congregational change had moved from the demographic determinism typical in Douglass writings to a greater appreciation of internal adaptiveness. Accordingly I looked at the relationship of four variables to membership growth for Protestant congregations. The four included: 1) 1990-2000 zip code population change -- as a typical measure of demographic influence; 2) the breadth of internal programming – one of the few internal factors noted by Douglass as holding potential for adaptation; 3) strictness – in appreciation for Kelley’s work and its reformulation by the socio-religious economists and 4) the use of electric guitars in worship – FACT2000’s best single measure of contemporary worship. Not surprisingly with over 11,000 Protestant cases, I found that all produced significant, zero order Pearson Correlation coefficients. They ranged from a low of .118 to a high of .272. None of these are particularly large, but at least the top two are strong enough to warrant attention. Perhaps most surprisingly, population change was at the bottom (.118) and breadth of internal programming at the top (.272). Strictness ranked second lowest at (.158) and electronic guitars ranks second highest at (.206). In further reflection on these findings I noted:

I have argued elsewhere that contemporary forms of worship, whose positive correlation with growth is even stronger in oldline Protestantism than conservative Protestantism, may be the first generally applicable adaptive strategy appearing in oldline Protestantism for the generationally carried social changes that have driven membership declines for over a quarter of a century. (Roozen 2001, forthcoming) To the extent that I am correct, I think that Douglass would be pleased to learn that two adaptive strategies sit at the top of our growth correlates. Social change may be the driver, but congregations are capable of adaptive responses. While strictness may have to be downgraded a notch, supply-siders and church leaders should nevertheless be pleased with the dominance of institutional factors. Those given to market models, however, should note as Douglass showed 70 years ago that supply can change through the adaptation of existing firms as well as the entry of entirely new firms.[22]

In a return engagement with the Religious Research Association in 2003 I used the FACT2000 data to wonder if there was a congregational equivalent to the apparent surge in individual spirituality.[23] Starting with one of the many end-of-the-millennium polls that found that 52 percent of all Americans pray every day and that 56 percent report that someone in their family usually says grace at family meals,[24] I discovered in the FACT2000 survey that a nearly equal 51 percent of all U.S. congregations reported giving “a great deal” of emphasis to personal devotional practices in their preaching and teaching and that 54 percent of U.S. congregations reported giving “a great deal” or “quite a bit” of emphasis to family devotions? The FACT2000 data also showed that oldline Protestants were less likely than persons from other faith groups to pray every day, were less likely to engage in family devotions, and indeed were less likely to engage in any of the home or personal religious practices mentioned in the FACT study. More importantly for present purposes the FACT2000 data indicated that the more emphasis a congregation gives to the values of home and personal religious practices the higher the congregation’s vitality and the more likely it is to be growing in membership; and that these results were evident within oldline Protestantism as well as within other faith groups.

Most recently Diana Butler Bass’s The Practicing Congregation combines an emphasis on spiritual practices with the internationality of mega-church pastor and best selling author Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Church to argue that the purportedly new form of church she describes may well constitute “the ‘most faithful and most hopeful’ possibility for renewal, vitality, growth, and spiritual and theological deepening” for oldline Protestantism.[25] In so arguing she highlights the value of intentional churches in general, but worries that much of what has recently been written about under this banner was too conservative to be genuinely oldline. In contrast she argues that the intentional “retraditioning” of Christian practices she has observed in some liberal congregations is the sub-type of purpose driven churches that “is most native to mainline Protestants, the pattern that grows from the soil of their experience, history, and traditions.”[26] She is especially direct in claiming that her practicing congregations are a necessary adaptation to the now failing, full-service, program model of congregation that church historian Brooks Holifield argues came to dominance in oldline Protestantism in the post-World War II period.[27]

Oldline Sources of Adaptive Vitality and Growth: The Empirical Test

Bass’ Practicing Congregation provides a wonderful, substantive starting point for guiding an empirical search for current, institutional sources (those internal to and therefore more under the control of a congregation) of oldline vitality and growth because, especially if one makes explicit the centrality of contemporary forms of worship in many of her “seeker” and “new paradigm” types of intentional congregations, she summarizes what can only be taken as the leading contenders. Specifically one finds internationality, contemporary worship, spiritual practices and the apparently now disposed former champion, the program church.

As good fortunate, or insightful foresight, would have it questions dealing with each of these areas were included, along with a measure of membership growth, in the FACT2000 national survey of American congregations. In addition to the substantive match of the survey to current interests, the huge overall number of responding congregations (14,301), provides a proportionately large number of responding oldline Protestant congregations (around 4,500) which makes this data set absolutely unique in its ability to sort out newly emergent types of congregations which may currently only exist in very small numbers.

As an initial foray I have combined the above named characteristics into the following six fold typology of oldline Protestant congregations and then simply looked at the percent of each type that was growing:

-

Congregations that reported high intentionality, regular use of contemporary worship and a strong emphasis on personal and familial spiritual practices ( Hi Int, HI CW & HI Pract in Figure 4)

-

Congregations that reported high intentionality and a strong emphasis on personal and familial spiritual practices but did not report regular use of contemporary worship ( Hi Int & HI Pract)

-

Congregations that reported high intentionality and the regular use of contemporary worship but did not report a strong emphasis on personal and familial spiritual practices

( Hi Int & HI CW)

-

Congregations that reported high intentionality but neither a regular use of contemporary worship nor a strong emphasis on personal and familial spiritual practices ( Hi Int Only)

-

Congregations that were highly programmatic, but did not report high intentionality (Hi Prog Only)

-

Congregations that were neither highly programmatic nor high intentionality (No Int & No Prog).

For the specific measurement of each of the variables that were combined to form this typology and the specific question used to measure membership growth, see Appendix 1.

Figure 4 shows the percent of growing, oldline Protestant congregations for each type. Two finding jump out of the graphic. Those congregations that are not distinguished by either intentionality or a strong programmatic thrust are considerably less likely to be growing (only 38%) than any of the other types. Those congregations distinguished by both high intentionality and high contemporary worship (with or without the further feature of high practices) are most likely to be growing, indeed nine in ten of such congregations. High intentionality and High program by themselves are an improvement over nothing, but lack the added boost provided by practices, and especially by contemporary worship.

Not shown in the figure are how many of each type there are. Perhaps most disconcerting from the perspective of the adaptive capacity of the qualities captured in the typology is that the FACT2000 survey finds that a full 75% of oldline Protestant congregations report being neither highly programmatic nor highly intentional. The comparable figure for evangelical congregations is 63%. Next most frequent are congregations which are highly programmatic, but not highly intentional – about 12% with both oldline and evangelical Protestantism. Then, highly intentional with a strong emphasis on spiritual practices -- 7.5% within the oldline, but nearly double that (13.4%) within evangelical Protestantism. Highly intentional congregations that regularly use contemporary worship are least frequent within the oldline (only 1.3%), but almost 9% within evangelicalism. The greater propensity of the oldline toward high intentionality and practices than toward high intentionality and contemporary worship lends some support to Bass’ contention that her practicing congregations may be the most natural path of oldline renewal. However, one has to wonder if (or how many of the) 7.5% percent of oldline Protestant congregations are highly intentional and practicing because of a recent retraditioning (ala Bass’ perspective) or because they have always been that way; and whether it makes a difference. The data also indicates that while there is a slight skew toward the social justice extreme among highly intentional, practicing, oldline congregations, one finds such congregations represented along the entire social justice continuum. Since “liberal” is an explicit component of Bass’ characterization of her practicing congregation, one has to wonder what difference this makes and about the extent to which she does this from a normative or an empirical perspective.

It appears that all of the recently distinguishing characteristics examined in Figure 4 -- internationality, contemporary worship, spiritual practices and the program church -- can be sources of oldline Protestant vitality and growth. But how do they compare to previously identified sources of growth and vitality. Among those for which we have measures in the FACT2000 are the following:

-

A highly relational ethos (as measured by close-knit family feeling),

-

How welcoming a congregation is of innovation and change,

-

Inspirational worship,

-

The size of the membership,

-

Population change in the congregation’s neighborhood (as measured by to 1990 to 2000 percent change in the total population in a congregation’s zip code area),

-

The presence or absence of serious conflict,

-

The number of social outreach programs,

-

Evangelistic outreach [as measured by having “special evangelistic programs), and

-

Strictness (measured by expectations for members).

See the Appendix for specific measures used.

Multiple regression is a common statistical method for assessing the relative influence of multiple factors. It provides a host of measures of association, the one I report here called the “part correlation.” It is a standardized measure of the unique affect of a particular variable on, in our case membership change, when the confounding influences of all the other variables in the regression have been removed from the total (zero order) association between the particular variable in question and membership growth, the higher the part correlation the greater the unique affect. For example, we know large congregations are more likely to be growing than small congregations. We also know that congregations with lots of programs are more likely to be growing than those with little programming, and that large congregations are most likely to have lots of programs. Question: Are large congregations more likely to be growing because they have lots of programs, or is there something about large size itself that is conducive to growth. The “part correlation” statistic generated by a multiple regression analysis tells us whether or not size matters independent of the influence of number of programs.

Figure 5 charts out the part correlation when the thirteen above noted variables are “regressed” on membership growth using oldline Protestant congregations. One immediate observation is that there are only nine variables (bars) in the chart. This is because four of the thirteen variables entered into the analysis did not have a statistically significant relationship with membership growth when the confounding influences of other variables were controlled. These four included: close-knit family feeling; special evangelism programs; number of social outreach program; and strictness. The latter is, of course, consistent with past research – strictness may differentiate oldline from evangelical congregations, but strictness does not seem to be related to growth and vitality within the oldline. In contrast, the insignificance of outward orientation (whether evangelistic or social ministry) calls into question a pet theory from little more than a decade ago.

A second immediate observation is that number of programs is one of the leading sources of growth (fifth of the top five) and that size appears to have a statistically significant, although small, influence independent not only of number of programs but also independent of quality of worship – quality of worship being another reason typically given for why large congregations have a growth advantage.

Then perhaps the most visually pronounced feature of the graphic is that the absence of serious conflict not only has the strongest relationship to growth, it is notably stronger than the next most important factor, namely having a clear purpose which is our measure of Warren and Bass intentionality. Rounding out the top five are population change and inspirational worship. Demographic change may not be as strong as it was forty years ago, but it is still a significant consideration.

Following the top five, although with yet another “step down” in strength of relationship are our two most “contemporary” factors – with contemporary worship nosing ahead of spiritual practices. Two things to note in the data about worship are that the inspirational quality of worship is slightly more important than having a contemporary style of worship, but that even controlling on the inspirational quality of a congregation’s worship, a contemporary style of worship still has a significant independent relationship with growth.

For a comparative perspective I ran the same multiple regression for the evangelical Protestant congregations in FACT2000 – see Figure 6. Perhaps the most striking visual cues in the graphic are, first, the absolute and relative strength of the absence of conflict – both considerably great that for oldline Protestant; and the general weakness of the rest of the relationships, especially in comparison to the oldline – that is, it is less clear what prompts growth in evangelical than in oldline congregations.

As was the case for the oldline Protestant results in Figure 5, some of the 13 regressed variables do not appear in the evangelical results shown in Figure 6 because they were not statistically significant. There are three: number of social outreach programs (also not significant in the oldline Protestant regression), and spiritual practices and contemporary worship. The latter two, were of course, highlighted in our analysis of the oldline, as was clear purpose which remains significant, although relatively weaker, in the evangelical regression. Why these three variables are uniquely important to growth and vitality in the oldline, but not evangelical Protestantism, is not readily evident in our analysis. It is true that all three are significantly more prevalent among evangelical congregations than among oldline congregations, which could account for some of the evangelical/oldline difference. But a more focused analysis will have to wait until another day.

It is also the case that some things were significant in the evangelical regression that were not in the oldline regression – specifically strictness, special evangelistic programs and the absence of a close-knit family feeling. The latter may strike many as surprising because close personal relationships are typically touted as a congregational strength; and indeed if one looks at the zero-order (i.e., uncontrolled) relationship between close-knot family feeling and growth it is positive. But when the confounding influence of other variables is removed, it turns out that the relationship reverses itself and that the flip side of “warm fuzzies’ asserts itself, namely the sharp and impenetrable edges of cliquishness. One sees the same reversal in the oldline regression, except that although negative, the part correlation never reaches statistical significant. That special evangelistic programs should be positively related to membership growth hardly seems surprising, and indeed the only apparent puzzle is why this only appears to be true for evangelical congregations and not for oldline congregations. Could it be the Protestant equivalent of “white men can’t jump?” Or perhaps it remains true that oldline congregations only turn to such kinds of programs when they are in a desperate state of decline (that is, being in decline causes one to try special evangelistic programs)? Why evangelism programs don’t appear to be a clear source of growth for oldline Protestant congregations remains to be answered, but mine is not the first study report the same absence of relationship.[28]

Oldline Sources of Adaptive Vitality and Growth: The Why

There are many perspectives from which to address the question of why the things identified in our oldline regression are sources of vitality and growth in the United States at the beginning of the 21st century. The limited space of a conclusion is not the place for an encyclopedic rending of either the possibilities or the specifics. But it does appear appropriate to remind ourselves as we come to the end of our analysis of the main theme that emerges from the research, and then to briefly suggest how each of the sources connects to it. The main theme: The change in both the rhetoric and the empirically verifiable reality about the fortunes of oldline Protestant congregations from demographic captivity to adaptive capacity. Yes the social context of the United States has changed dramatically in the last half century, continues to change, and it is absolutely clear that this change is culpable in the now forty continual years of oldline decline. But the good news is that unlike past theory and research that stressed the oldline as helpless victim; the most recent research including that of this chapter strongly suggests that there are things a congregation can do to adapt to the contextual changes. The contextual changes are complex and obviously vary in intensity by specific locale. But there is nevertheless a general agreement among social analysts that we are somewhere in the early stages of a major socio-economic-cultural transition, variously labeled as late- or post-modernity. Among other things it is a merging of the demographic and value changes carried in and by the post-war generation, with the electronic, economic and cultural changes of globalization.[29] Assuming this to be the case, then my concluding reflections briefly, but specifically, address the question of how each of the major, institutionally controllable sources of vitality and growth identified in Figure Five – the oldline Protestant regression – might be adaptive to late- or post-modernity.

Absence of Serious Conflict: Postmodernity is characterized by an increasing awareness of and affirmation of diversity, and correspondingly an increasing politicalization of institutional decision making in all major sectors of society including religion.[30] One implication of this for congregations is an increasing amount of conflict. What our regression suggests is that a near necessity for vital congregations today is the ability to either contain conflict or channel it toward constructive purposes. That it is more a matter of a congregation’s ability to deal with conflict than a matter of the total absence of conflict is supported by FACT2000 data that shows almost no difference between growing and declining oldline Protestant congregations in the amount of low levels of conflict, but a huge difference in the amount of serious levels of conflict.

Clarity of Purpose (Intentionality and Purposefulness): From a marketing perspective, the postmodern world is a world of niches and a world of choice. Uniqueness sells at a premium to be sure, but minimally a consumer with options is going to gravitate toward products that clearly address one’s interests over those where the connection is vague or ambiguous. From a production perspective, the organizational advantages of a clear purpose that have long been recognized in the field of organizational development and well summarized in The Purpose Driven Church (not the least of these being in regard to conflict management) take on added significance during periods of cultural unsettledness precisely because the comfortable and often taken-for-granted patterns of the past can no longer be counted on.

Inspirational Worship: Given the centrality of worship for congregations, it hardly seems worth noting that the quality of worship might be a source of vitality. But there is a growing awareness that either a taken-for-grantedness about or other priorities distracted oldline Protestantism from this seeming truism during much of the last forty years.[31] The connection of this distraction to post-modernity is probably less direct than for other sources on our list. However both quality and “inspiration” attract a premium in the postmodern world, so to the extent that the distraction led to a drop-off in quality and/or that more, habitual “pedagogical” models of worship dominated more “inspirational” emphases, one can see postmodern implications.

Extensiveness of Program: In a world of difference, diversity, and choice, it seems self-evident that the broader array of options a congregation has to invoke participation and express commitment the greater the number of constituencies that the congregation can attract and sustain. This was the genius of the modern program church; its genius is geometrically amplified in a postmodern world, and the mega-churches had taken the expression of program church to a new level.[32]

Contemporary Worship: Contemporary worship is typically characterized by an informality and style of worship music that takes its cues from the baby boomer generation. The research of the 1970s was absolutely clear that the onset of the oldline declines in the mid-to late 1960s was primarily due to an inability of congregations to retain or attract baby boomers as young adults. The reasons for this are too complex to elaborate here, especially since excellent treatments of the subject are readily available.[33] But the more important and related question for present purposes is whether or not oldline congregations that use a contemporary style of worship are able to attract and/or retain younger members. Certainly the antidotal evidence of this is plentiful, and the FACT2000 data confirm it. Of the six “Program-Intentionality-Contemporary Worship-Spiritual Practice” types of oldline Protestant congregations analyzed in Figure 4, those regularly using contemporary worship have the largest numbers of young adults and lowest number of older adults. The Program type is next most likely to have large numbers of young adults, although a distant second. Those congregations emphasizing spiritual practices are next, with those congregations not distinguished by any of the traits represented in Figure 4 representing the opposite extreme – least numbers of young adults and largest number of older adults.

Spiritual Practices: Building on earlier arguments about the centrality of change from an objectified, external to self-expressive, internal locus of authority implicit in the increasing dominance of religious consumerism as a form of cultural individualism,[34] and the connection of this change to the baby boomer’s preference for spirituality over organizational religion,[35] I have most recently argued that the most profound and foundational of the religious transitions related to post-modernity is the change in religious expression from a grounding in the “Word” to a grounding in the “Spirit.”[36] In making this argument I demonstrated the significance of the shift by showing that even when we separately examine Old-line and Conservative Protestantism, for example, we find higher levels of vitality among the more expressive denominations (e.g., Episcopal and Unitarian Universalist with old-line Protestant) than among the more cognitive (e.g., Presbyterian and UMC with old-line Protestantism). The importance of spiritual practice as a source of vitality in oldline Protestant congregations found in the empirical analysis presented above is a further manifestation of this consequence of postmodern adaptability.

I concluded my 2003 article signaling the importance of home and personal spiritual practices by noting: “the FACT data clearly report that vital congregations not only practice what they preach—they also preach about home and personal religious practice.”[37] Preaching, of course, is an exercise in internationality so unwittingly I further signaled another of the key contemporary sources of oldline vitality. The research presented above adds two further images to this appropriately postmodern montage on oldline vitality. Vital oldline congregations not only are practiced at programming; they also program their practices. And, a very small but growing segment of the most venturesome experiments in oldline vitality seek to praise God and inspire themselves not with an organ-guided rendition of “Rock of ages,” but an electronically amplified, “We will rock you!”

APPENDIX

FACT 2000 Oldline and Evangelical Protestant Denominations

The following denominations are included in the FACT 2000 data:

Oldline Protestant: Episcopal, Presbyterian, Unitarian-Universalist and United Church of Christ; American Baptist, Disciples of Christ, Evangelical Lutheran, Mennonite, Reformed Church in America and United Methodist.

Evangelical Protestant: Assemblies of God, Christian Reformed, Nazarene, Churches of Christ, Independent Christian Churches (Instrumental), Mega-churches, Nondenominational Protestant, Seventh-day Adventist and Southern Baptist.

The following denominations and faith groups were also included in the FACT survey, but there data are not used in the articles’ multivariate analyses: The Historic Black Protestant denominations, Roman Catholics, Orthodox, Bahai, Mormon, Jewish and Muslim

Download the FACT 2000 Measures

Footnotes

[1] Kelley, Dean M. 1972. Why Conservative Churches Are Growing. San Franscisco: Harper & Row.

[2] Two of the foundational publications of the movement include: McGavern, Donald A. 1970. Understanding Church Growth. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans; and Wagner, C. Peter. 1976. Your Church Can Grow. Glendale, CA: G/L Regal Books.

[3] Hoge, Dean R. and David A. Roozen, eds. 1979. Understanding Church Growth and Decline: 1950-1978. New York: Pilgrim Press.

[4] See, for example, the apologetic included in Douglass, H. Paul and Edmund deS Brunner. 1935. The Protestant Church as a Social Institution. New York: Harper and Brothers.

[5] Smylie, James H. 1979. “Church Growth and Decline in Historical Perspective: Protestant Quest for Identity, Leadership and Meaning. Pp. 69-93 in Understanding Church Growth and Decline: 1950-1978, edited by Hoge and Roozen. New York: Pilgrim Press.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Roozen, David A. and C. Kirk Hadaway, eds. 1993. Church and Denominational Growth. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

[8]Oldline Protestant denominations included in Figures 1 & 2: Episcopal, Presbyterian-USA, United Church of Christ, Christian Church-Disciples, Church of the Brethren Evangelica Lutheran-ELCA, Reformed Church of America, United Methodist. Evangelical Protestant denominations included in the figures: Baptist General Conf, Christian&Missionary All, Cumberland Presbyt, Evangelical Covenant Church, Lutheran Ch, Missouri Sy, N.A. Baptist Conf, 7th Day Adventist, Southern Baptist Conv, Wisc Evang Lutheran Sy, Assemblies of God, Church of God-Anderson, Church of God-Cleveland, Church of Nazarene, Free Methodist of N.A., Salvation Army.

[9] See Appendix for the FACT 2000 list of oldline and evangelical Protestant denominations

[10] Unfortunately, trend data over any significant time period for any measure of vitality at the congregational level other than membership growth is not readily available so that any claim to more or less at the current time in any of these other areas is, at best, impressionistic).

[11] The Protestant Church.

[12] Kelley, Dean M. 1972. Why Conservative Churches Are Growing. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

[13] Understanding Church Growth.

[14] Your Church Can Grow.

[15] Iannaccone, Laurence R. 1989. “Why Strict Churches Are Strong.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Salt lake City, Utah.

[16] Finke, Roger and Rodney Stark, The Churching of America, 17766-1990: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy, Rutgers University Press 1992.

[17] Church and Denominational Growth, p 129

[18] Ibid, p 133

[19] Miller, Donald E. 1997. Reinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New Millennium. Berkeley: University of California Press. Hadaway, C. Kirk and David A. Roozen. 1995. Rerouting the Protestant Mainstream: Sources of Growth and Opportunities for Change. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

[20] Roof, Wade Clark, A Generation of Seekers: The Spiritual Journeys of the Baby Boom Generation. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. 1993; Peter A. R. Stebinger, Congregational Paths to Holiness, Hartford Institute for Religion Research Working Paper 95-1, 1995; Nancy T. Ammerman and AdairLummis, Spiritually Vital Episcopal Congregations. Report to Trinity Grants Board. 1996;

[21] Columbus, Ohio, October 19-21, 2001. Subsequently published as: “10,001 Congregations: H. Paul Douglass, Strictness and Electric Guitars. “ Review of Religious Research, vol 44:1, 2002. Also available online at: http://hirr.hartsem.edu/bookshelf/roozen_article3.html

[22] “10,001 Congregations;” Roozen, “2001” reference is to Roozen, David A., “Worship and Renewal: Surveying Congregational Life.” The Christian Century, June 5-12, pp. 10-11, 2002.

[23] “FACTs about Personal Religious Practice: Meeting Evangelicals Halfway,” Norfolk, VA October 24-26, 2003. Subsequently published online: http://fact.hartsem.edu/topfindings/topicalfindings.htm

[24] Cited in “75% say God answers prayers,” by Thomas Hargrove and Guido H. Stempel III, distributed by Scripps Howard News Service, December 28, 1999. www.shns.com.

[25] Diana Butler Bass, The Practicing Congregation: Imagining a New Old Church, Herndon, VA: The Alban Institute, 2004, p 19. Rick Warren, The Purpose Driven church: Growth Without Compromising Your Message & Mission, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1995.

[26] The Practicing Congregation, p 19.

[27] Holifield, E. Brooks. 1994. “Toward a History of American Congregations.” Pp. 23-53 in American Congregations, Vol 2: New Perspectives in the Study of Congregations, edited by James P. Wind and James W. Lewis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. University of Chicago Press.

[28] Marjorie H. Royle, “The Effect of a Church Growth Strategy on United Church of Christ Congregations,” pp 149-154 in Church and Denominational Growth.

[29] See, for example: Wade Clark Roof, Jackson W. Carroll and David A. Roozen (eds). The Post-War Generation and Religious Establishments: Cross Cultural Perspectives. Boulder: Westview Press. 1995; and Rengger, N.J., Political Theory, Modernity and Postmodernity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995).

[30] For a brief elaboration of this in relationship to oldline Protestantism see the section on “From Prophetic to the Political,” in David Roozen, “Four Mega-Trends Changing America's Religious Landscape” A presentation at the Religion Newswriters Association Annual Conference, September 22, 2001. Available online: http://hirr.hartsem.edu/bookshelf/roozen_article4.html. For a more extended discussion of this reality at the national denominational level, see David Roozen, “National Denominational Structures’ Engagement with Postmodernity: An Integrative Summary from an Organizational Perspective,” in Roozen & Nieman (eds), Church, Identity, and Change: Theology and Denominational Structures In Unsettled Times, Eerdmans, Forthcoming, January, 2004.

[31] See for example the section, “ From Mission to Worship” in “Four mega-Trends.”

[32] See, for example, two online articles by Scott Thumma: “Megachurches Today: A Summary of data from the Faith Communities Today Project.” http://hirr.hartsem.edu/org/faith_megachurches_FACTsummary.html; and, “Exploring the Megachurch Phenomena” http://hirr.hartsem.edu/bookshelf/thumma_article2.html

[33] See, for example, Understanding Church Growth; Church and Denominational Growth and A Generation of Seekers.

[34] Penny Long Marler and David Roozen, "From Church Tradition to Consumer Choice: The Gallup Surveys of Unchurched Americans," pp 253-276 in Church and Denominational Growth.

[35] A Generation of Seekers: The Spiritual Journeys of the Baby Boom Generation

[36] “Four Mega-Trends.”

[37] “FACTs about Personal Religious Practice: Meeting Evangelicals Halfway.”

|