Recent Shifts in America’s Largest Protestant Churches:

Megachurches 2015 Summary Report

by Scott Thumma and Warren Bird

Download a copy in PDF format for easier reading and printing.

Introduction

Amid reports from America’s largest Protestant churches of scandals or decline after pastoral transitions, many have speculated about their health and future vitality. Our 2015 survey of megachurches,1 the fifth such survey since 2000 that our two organizations2 have created and fielded, directly addresses this topic of vitality and related trends that are shaping these largest churches, and indirectly influencing all other congregations as well.

This executive summary highlights the noteworthy trends and also the troubling challenges evident in the 2015 megachurch survey results. Much of this report addresses the issues that survey participants stated they hoped to learn from the survey. For greater detail of these and other results of individual questions see the survey frequencies.3 Additionally, smaller focused reports about multisite churches, outreach efforts to young adults, measures of vitality and growth and succession will be released individually over the coming months.4

General Profile of 2015 Megachurches

The very largest U.S. churches draw more than 30,000 to worship each weekend, and the smallest megachurch, by widely accepted definition, attracts 2,000 adults and children (all physical campuses combined). The median5 weekly attendance in 2014 for our sample was 2,696; a figure quite similar to the median attendance size of megachurches in 2010, with a median of 3,800 persons for the larger group of those who regularly participate in the life of these churches.

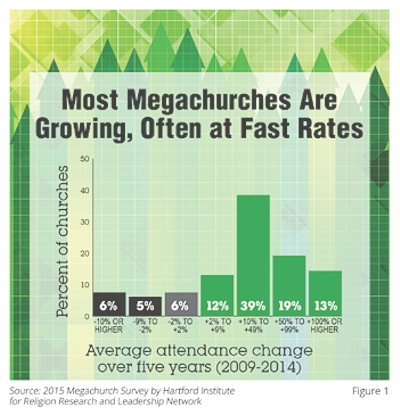

Rapid growth remains a hallmark of very large congregations (see Figure 1). The median growth rate was 26% over five years – so over 5% a year on average. Nearly three-quarters (70%) of them increased by 10% or more in the past five years. For 23% of the attendance varied only slightly (between -9% and +9% change) over the past five years, and 6% of surveyed churches declined by 10% or more in those five years.

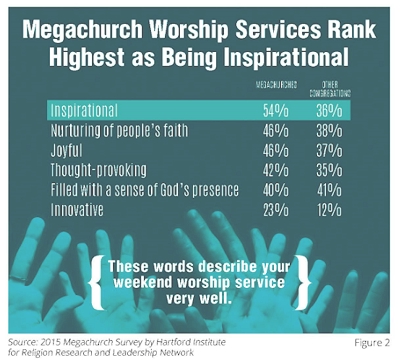

Megachurches offer on average five services a weekend, with about half the churches (45%) reporting that the style of these services varied considerably. Additionally, many of the megachurches (62%) are distributed across multiple locations (multisite) and some even host an online campus (30%). Overall, the worship at these very large churches continues to be contemporary (including electric guitars, bass, keyboard and praise band), highly technological (having projection, large screens, sound boards, and wifi) and is self-described as inspirational, joyful, nurturing of faith, thought-provoking, and filled with sense of God’s presence (see Figure 2).

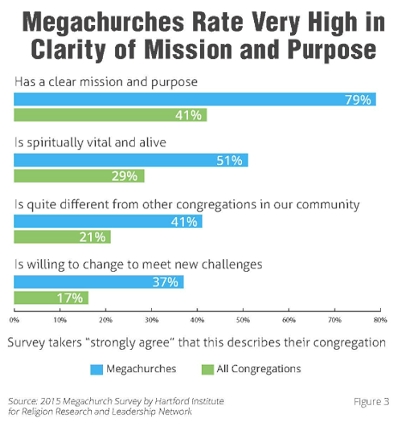

These churches continue to offer a wide array of programs for members and have significant outreach to the larger community. Compared to a majority of smaller congregations6, the contrast is both dramatic and significant. As Figure 3 indicates, megachurches are almost twice as likely to say they have a clear mission and purpose (41% vs 79%), be seen as different from other churches in their area (41% vs 21%) and say they are spiritually vital and alive (51% vs 29%). They strongly emphasize evangelism, personal spiritual practices and living out their faith in everyday life. The membership of megachurches is significantly younger and more racially diverse than smaller congregations as well.

A majority of these largest churches are still connected to a denomination, but the ties to these denominations are often weak, seen as unimportant to their members and seldom replied upon for resources or assistance. Most very large churches also affiliate with informal networks of churches in additional to their denominational ties.

Noteworthy Continuing Trends

• Congregations are continuing to reach megachurch status

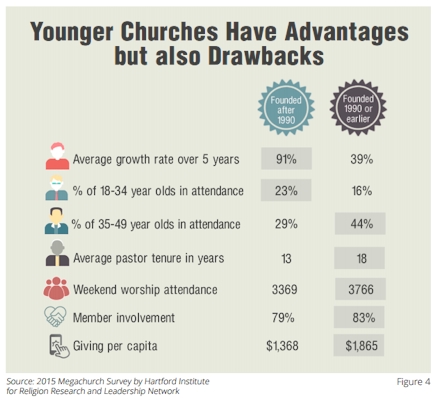

Over the past five years the median founding date increased from 1972 to 1977; thus the megachurch phenomenon hasn’t waned; newer and younger churches are regularly growing to megachurch size. The overall list of megachurches in the U.S., privately compiled by Leadership Network and the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, has seen a net increase of 39 in the last half decade. Likewise, the churches that were founded since 1990 look considerably different than the megachurches founded earlier (see Figure 4). These younger churches are growing at a far more rapid rate in terms of percentage and numerically (91% vs 39%), are led by younger pastors with shorter tenures, are described as being more spiritually vital, use technology more effectively and have a greater percentage of young adults than the older megachurches. On the other hand, those churches founded in 1990 or prior are larger, claim to have more member involvement and greater giving per capita by $500/person.

• Increasing numbers of churches are adopting a multisite strategy

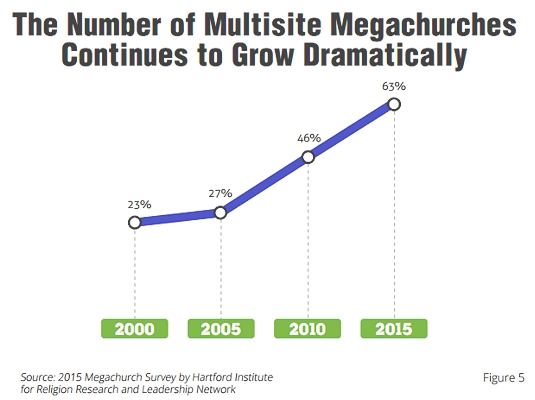

In 2010, 46% of megachurches were multisite, and now five years later that has grown to 62% of very large churches, with another 10% contemplating about this approach (see Figure 5). Additionally, the average number of locations a multisite church has increased from 2.5 to 3.5 per church. This has had the effect of increasing the number of worship services held per church. This phenomenon has, however, reduced the size of the main sanctuary from 1,500 seats to a median of 1,200. Multisite churches have smaller sanctuaries on average, but nearly double the attendance of single-site churches. As such, a church can maintain a smaller physical size, grow larger and, as evidenced by the survey findings, grow faster than single-site megachurches.

• Small groups remain critical to success

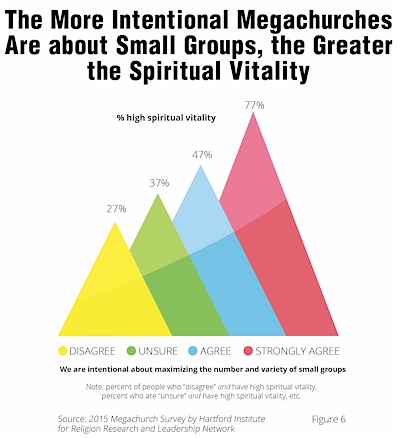

Megachurches continue to have a very high level of intentional use of small groups. Seventy-nine percent say it is central (slightly less than in the 2010 survey) and that they are intentional about maximizing the number and variety of small groups they offer. A median of 40% of the adults in these congregation are involved in small groups. Having such groups is highly beneficial; those which are intentional about the practice are much more likely to report being spiritual vital (see Figure 6). It is also important to realize that small groups alone are not the only strategy used to connect and mature their members. Half the megachurches also use Sunday School (with a median of 34% of members participating), three-quarters (79%) of them offer age-graded children and youth worship services concurrent with adult services, and a sizable majority (70%) use their building’s informal spaces during service to reach those who might linger on the margins rather than actively participate in the services.

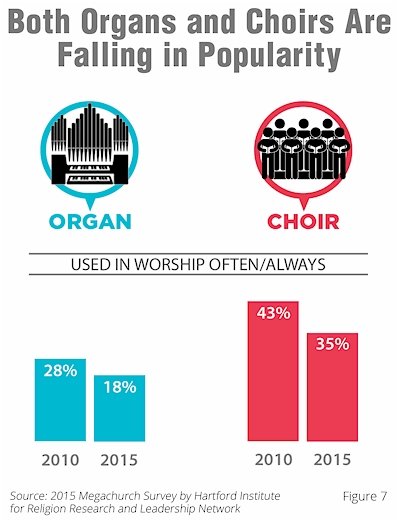

• Traditional worship features continue to decline

The use of organ used often or always in worship services fell from 28% to just 18% of all megachurches (see Figure 7). Likewise, having choirs perform in services often or always declined from 43% to 35% of congregations (Figure 7 again). On the other hand, an increasing percentage of churches say that Communion is always or often a part of worship, rising from 51% in 2010 to 57% presently.

• Use of online campuses is rising

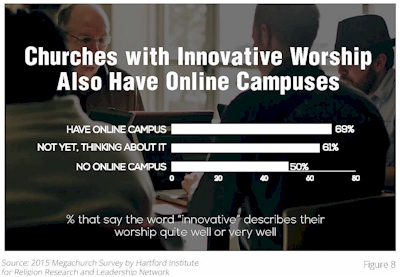

Currently 30% of megachurches offer an online campus experience—described as more than video streaming of the service, including interactive features, staff involvement and online attender accountability—and 18% more are considering this approach. Half of these began their online campusin 2012 or later. Roughly one in three (36%) of them have at least one full-time staff person dedicated to this“campus” which on average serves a median of 300 persons weekly. This effort goes hand in hand with other significant uses of technology. While this tech use is already very high to begin with, megachurches are now

employing more interactive uses of technology in worship. Image magnification and video clips in service are shared by three-quarters of megachurches, with the interactive use of social media during sermons illustrating

the growing edge of technology for roughly 20% of the very large congregations. Likewise innovative worship and online campuses are related, as Figure 8 shows.

• Significant involvement in missions, world missions, and social outreach

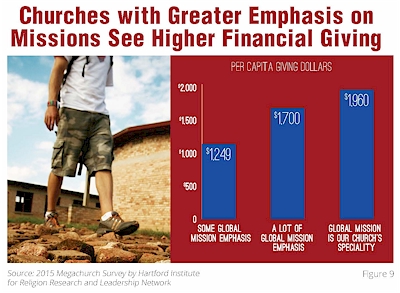

Global mission programs are a major emphasis or a specialty of the congregation for 81% of megachurches. Likewise, giving to all missions

has increased by 4% in the budget to median of 14% as compared to the 2010 and 2008 studies where the median was 10% both years. Additionally, having a major emphasis on engagement in community service

programs has grown by 7% to 81% of megachurches in 2015 compared to 74% of them in 2010. See Figure 9 for additional financial comparisons.

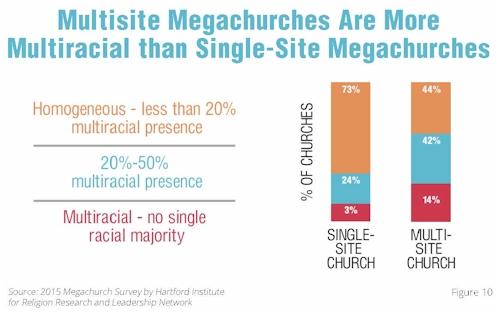

• Many megachurches are significantly multiracial

In 2015, 10% of megachurches claimed to have no racial majority; this is up slightly from 2010 but nearly identical to what we found ten years ago in 2005. Additionally, 37% of churches surveyed had between 20% and 49% minority presence in what was often, in our survey, a majority Caucasian congregation. Interestingly, multisite megachurches are more multiracial than single-site churches (see Figure 10); however, it is impossible to tell from the data whether this diversity is within the sites or separates out across the different locations.

• Mentoring and leadership development seen as key

Three-quarters of churches (72%) have an internship or mentoring program, whereas in 2008 only 69% did. The approximate length of the average internship program is 12 months and 25% of these are done in conjunction with a recognized seminary.

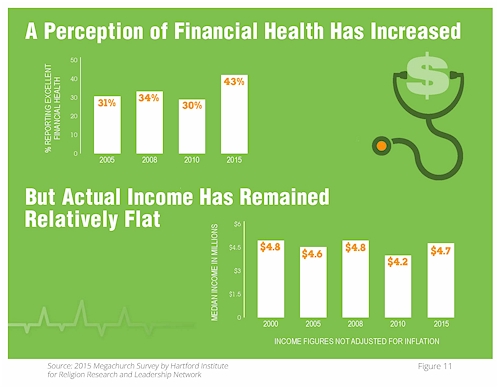

• Finances have rebounded significantly following the Great Recession

The median income of megachurches in 2014 was $4.7 million, a figure greater than the reported median income in 2009 even if it were adjusted for inflation. However, this median income amount hasn’t dramatically changed since 1999 when we first began collecting financial data. Thus, if inflation were factored in, megachurches are actually bringing in less income in real dollars over the past 15 years. Had they kept pace, they would currently be reporting a median of $6.5 million to maintain a commensurate giving level plus inflation. On the other hand, 43% of churches report their financial health is excellent now; whereas only 30% reported that in 2010. The historical perspective shows this to be a significant increase over the past 10 years, and quite a rebound from the Great Recession that peaked in 2008. See Figure 11 for more details.

Ongoing Challenges

Often megachurches are perceived as having a world of advantages over smaller congregations. Their relative numerical success often masks other dynamics that pose real challenges for a large church’s leadership team. The previous discussion of stagnant income levels for the past 15 years is one indication that significant member growth does not eliminate all difficulties within congregational dynamics. Findings from the current survey highlight a number of the more serious megachurch challenges. It is critical, however, to remember that these ongoing challenges are not just felt by very large churches but plague all congregations alike whether big or small.

• Promoting the active engagement of participants

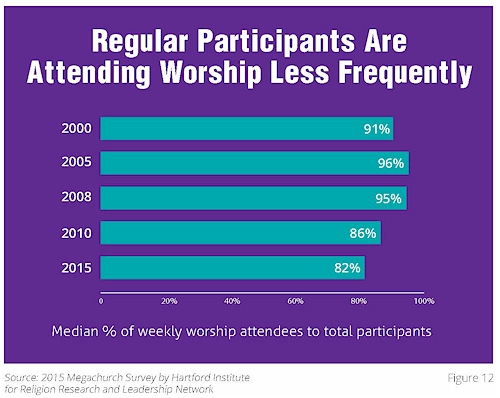

It is a known fact that the larger the group, the more difficult it is to engage those participants in the active life of the congregation. Based on the 2015 survey, the

median attendance declined very slightly since 2010, but the median number of what church leaders describe as regular participants grew by nearly 600. It is impossible to know from this survey exactly the cause of this finding, but it does follow a pattern observed in congregations of all sizes that regular members are attending less frequently – those who once came every week are now as likely to attend 2-3 times a month as they are every week. This “less frequent” attendance pattern might account for a larger number of regular participants but not a corresponding increase in median weekly attendance.

In an effort to explore this further, we created a variable examining the percentage of weekly attenders to total participants, what we label as the average active/engaged ratio (expressed as a percent). For the megachurches in the 2015 survey this average active/engaged percent was 82%. This percentage has changed somewhat over the five national surveys we conducted, declining slightly for the last two, as the earlier regular participant and weekly attendance comparison might imply (see Figure 12).

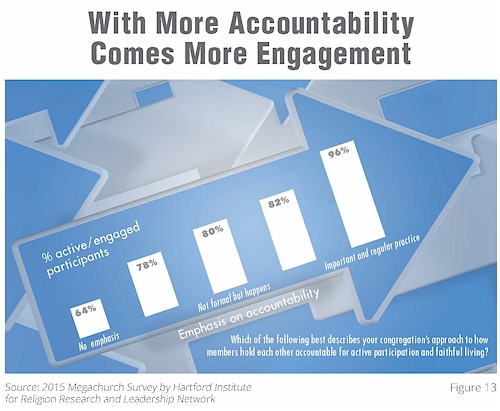

The connection between attendance and involvement is a crucial issue for any church, and especially for these very large congregations. Having a high percentage of robust actively engaged members enhances many congregational dynamics. The greater this percentage of total participants as active attendees, the larger the per capita giving amount. Likewise, there is a positive correlation between the percentage of active persons and the percent of members in small groups. Additionally, churches that implement intentional systems of member accountability show significantly higher levels of participation (see Figure 13).

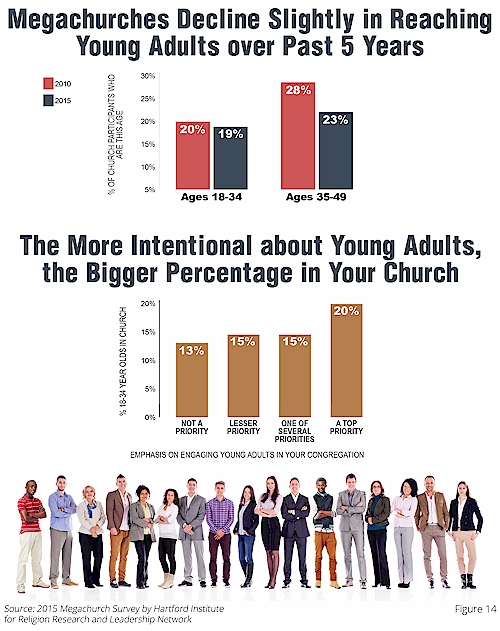

• Continuing to attract, maintain and minister to young adults

Megachurches are leaders in attracting young adults compared to smaller congregations, yet even they garner a smaller percentage of 18-34 year olds (19%) than is found in the general U.S. population (23%). There has also been a very slight decrease in the percentage of this age group and more so those in the 35-49 year old category since the 2010 survey (see Figure 14).

Nevertheless, 64% of megachurches report an increase in young adults in the past three years. This might imply that holding onto their young adults challenges very large churches, as much as it does other congregations. Half of megachurches say they emphasize young adult programs, although 86% of these churches emphasize programs for 13-17 year olds. Of these churches, sixty-eight percent of megachurch leaders say their programs for 18-34 year olds are a top or a main ministry priority. Giving young adult ministry a priority status makes a difference; the more a church is intentional about young adult ministry, the larger percentage

of them it will have in the congregation (see Figure 14 again).

Interestingly, there is significantly more church support of young adult programs focused on engagement, pre-marital and marriage efforts than for singles programming. This may show that the desire of church leadership is to recruit married couples or promote young-adult marriages. Yet the latest data on young adults in America shows they are waiting longer to marry and even longer to have children7. The demographic reality is that two-thirds of 18-34 year olds in the US population are single. Yet among the young adult population of the megachurches surveyed, only one third (33%) are estimated to be single.

• Denominational and congregational connections matter less

The percentage of nondenominational megachurches has remained consistent at about 40%. For the denominationally-affiliated megachurches, however, a new battery of survey questions reveals that their ties with denominations are relatively insignificant. Two-thirds reported their denominational identity and affiliation was not very or not at all important to their congregation. Likewise, denominational assistance was not used or was rated as not at all helpful in their efforts to change and adapt for a vast majority of churches (85%). Thirteen percent considered leaving their denomination in the past 10 years and half of those actually did. This move away from denominational connections is not worrisome in itself, unless you happen to be a denominational executive.

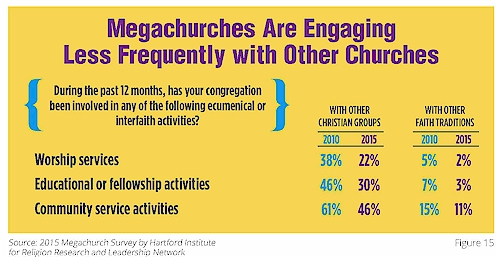

However, this shift toward independence can also be seen in their involvement with other congregations (see Figure 15). A smaller percentage, as compared to 2010, reported being involved with other Christian groups and with congregations of other faith traditions, in past 12 months for worship, education, fellowship or community service.

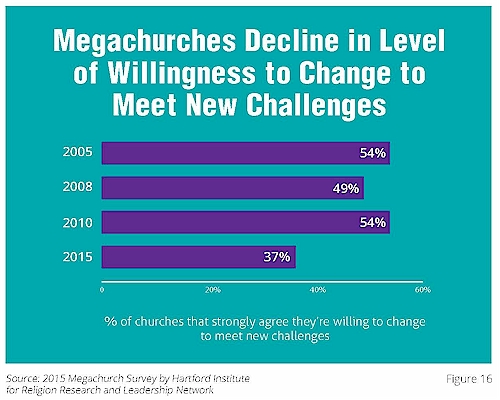

• Sustaining innovation and the willingness to change

Innovation and willingness to change are strongly correlated to growth and health. Both these characteristics are always strong components of megachurches, as compared to smaller churches. Yet figures from the 2015 megachurch study show dips in scores related to both these characteristics. Ten percent fewer respondents indicated that describing their worship as innovative fit them very well compared to five years ago. Barely a third (37%) of churches in 2015 strongly agreed they were willing to change to meet new challenges whereas 54% did so in 2010 (see Figure 16).

• Maintaining vitality as pastoral age and tenure increase

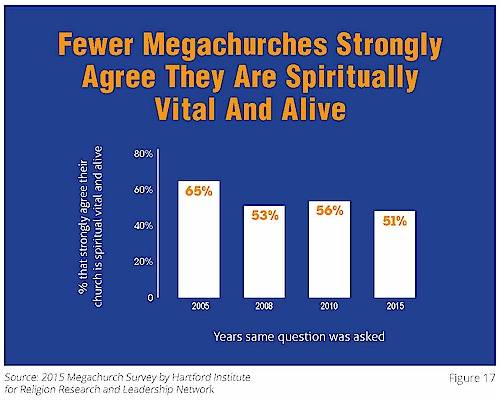

A majority of megachurches continue to strongly agree that their congregations are spiritually vital and alive, although this percentage has declined somewhat over the past 10 years (see Figure 17).

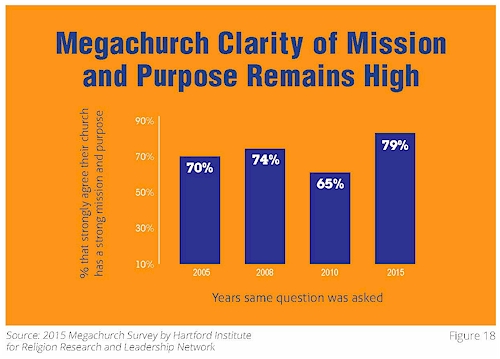

On the other hand, their sense of purpose and having a clear mission has remained strong and even increased (see Figure 18).

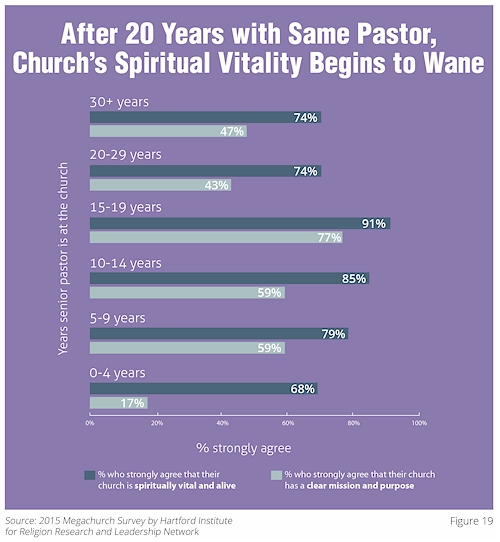

Yet an interesting correlation arises as these characteristics are examined taking into account the senior leader’s age and length of time at the megachurch. The increasing tenure of the senior pastor is negatively related to spiritual vitality and a clear mission and purpose of the church (see Figure 19).

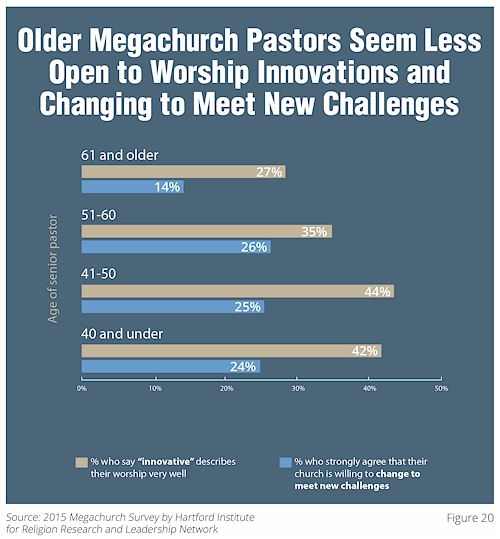

Likewise, the older the senior leader the less likely they are to identify their worship as innovative or to see the church as constantly changing to improve and adapt (see Figure 20). In other words, the older the senior pastor is and the longer at the church, the greater likelihood that the church will routinize and become less flexibility within an ever-changing cultural context.

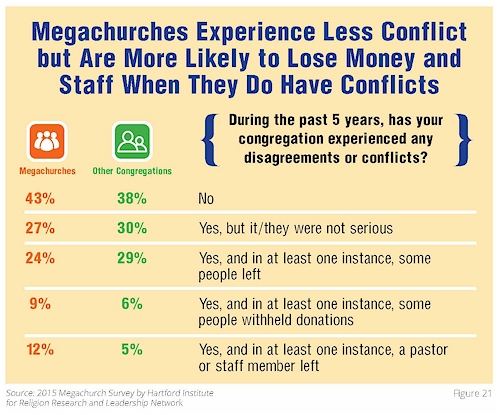

The 2015 survey was the first time we asked extensive questions about the level of conflict in megachurches (see Figure 21). And indeed there is some, not to the level of all congregations in certain cases but in terms of

members withholding money or a pastor or staff person leaving megachurches have a great percentage of conflict.

• Planning for a smooth succession

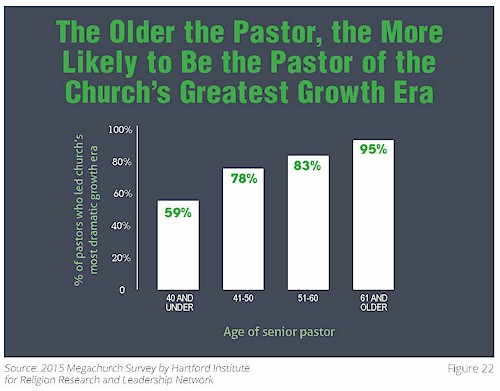

Much like previous large church surveys, 80% of current megachurch senior pastors are the pastors under which the greatest numerical growth occurred. Many of these senior clergy are nearing retirement age: 20% are over the age of 60, and 5% of that group are 65 or older. But this is more significant when examining the percentage of oldest senior pastors who are also the person responsible for the growth; fully 95% of those over 60 are also the person who led the church through tremendous growth (see Figure 22).

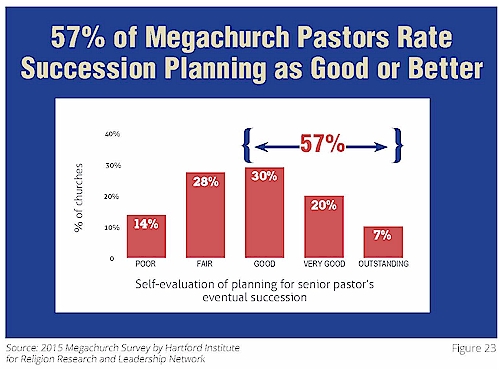

It is clear from this data that succession should be a significant issue for these churches. While more than half (57%) rate the succession planning efforts as good or better, a sizable group (43%) indicate concern that

succession planning is only poor or fair (see Figure 23).

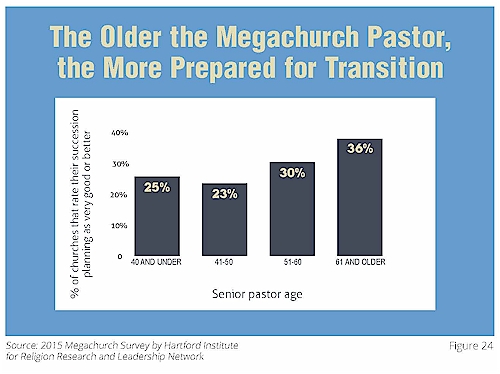

A percentage of churches begin to plan early but the need becomes greater as the senior pastor progresses toward retirement age. And the older the pastor, the higher the percent of churches that rate their

planning as very good or outstanding (see Figure 24).

What’s Next

The largest-attendance Protestant churches in the United States remain strong and vital in how they self-assess themselves on a number of issues. At the same time, these very large churches face many of the same challenges as congregations of other sizes. Additionally, their large size makes aspects of their religious work that much more difficult, such as creating commitment, community, and member engagement. This report hints at a number of patterns evident in the findings that provide possible paths for strengthening many of these critical facets of ministry.

Much more remains to be learned from the survey findings about these and other dynamics. Further reports will be released in the coming months to explore several of these challenging issues in depth and offer possible approaches to addressing them that are not just crucial to megachurches but to churches of all sizes.

Forthcoming topics will include deeper analysis of:

• What the survey shows about methods of increasing young adult participation.

• What the survey shows in terms of increasing member engagement.

• How various measures of vitality correspond to congregational growth rates.

• The apparent differences between church that are being led by the first pastor of growth and subsequent

senior pastors.

• How multisite and single-site churches are similar and different.

About the Authors

Scott Thumma, Ph.D., is Professor of Sociology of Religion at Hartford Seminary and leads its D.Min. program. He is director of Hartford Institute for Religion Research and coleads the Faith Communities Today research project. Scott has published many articles and chapters in addition to co-authoring three books, The Other 80 Percent: Turning Your Church’s Spectators into Active Participants, Beyond Megachurch Myths and Gay Religion. His research focuses on megachurches, the rise of

nondenominationalism and the impact of the Internet on congregational dynamics. Follow him on Twitter @sthumma Scott Thumma, Ph.D., is Professor of Sociology of Religion at Hartford Seminary and leads its D.Min. program. He is director of Hartford Institute for Religion Research and coleads the Faith Communities Today research project. Scott has published many articles and chapters in addition to co-authoring three books, The Other 80 Percent: Turning Your Church’s Spectators into Active Participants, Beyond Megachurch Myths and Gay Religion. His research focuses on megachurches, the rise of

nondenominationalism and the impact of the Internet on congregational dynamics. Follow him on Twitter @sthumma

Warren Bird, Ph.D., is Research Director at Leadership Network. With background as a pastor and seminary professor, he is author or co-author of 28 books for ministry leaders including Teams that Thrive: Five Disciplines of Collaborative Church Leadership with Ryan Hartwig, and Next: Pastoral Succession that Works with William Vanderbloemen. Follow him on Twitter @warrenbird. Warren Bird, Ph.D., is Research Director at Leadership Network. With background as a pastor and seminary professor, he is author or co-author of 28 books for ministry leaders including Teams that Thrive: Five Disciplines of Collaborative Church Leadership with Ryan Hartwig, and Next: Pastoral Succession that Works with William Vanderbloemen. Follow him on Twitter @warrenbird.

About Hartford Institute for Religion Research

Hartford Seminary’s Hartford Institute for Religion Research, founded in 1981, has an international reputation as an important bridge between the scholarly community and the practice of faith. Its work is guided by a

disciplined understanding of the interrelationship between the life and resources of American religious institutions and the possibilities and limits placed on those institutions by the social and cultural context in which

they work.

About Leadership Network

Leadership Network’s role is to foster innovation movements that activate the church to greater impact for the glory of God’s name. The nonprofit founded in 1984 now serves over 200,000 leaders all over the world.

See leadnet.org.

Endnotes

1 A megachurch, by widely accepted definition, is a Protestant church that regularly draws a weekly worship

attendance of 2,000 or more (adults and children). If the church is multisite, this involves all physical campuses combined.

2 Scott Thumma is associated with the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, Hartford Seminary,

www.hartfordinstitute.org. Warren Bird is associated with Leadership Network, www.leadnet.org.

3 For a copy of the 2015 Survey of Largest U.S. Churches with response frequencies, see www.hartfordinstitute.org.

4 The Survey of Largest U.S. Churches received 209 usable responses (a 13% rate) which was then weighted by region and size against the full census of megachurches in the US based on the comprehensive

listing of Hartford Institute and Leadership Network. This report includes churches of 1,800 or above in

weekly worship attendance, rather than the typical 2,000 cutoff to maintain consistence with previous

reports and because weekly attendance in these churches can vary by several hundred.

The survey was launched 4/15/15 and closed 7/14/15. It was conducted by email only, with a different

reminder sent every two to three weeks to those who had not responded, later in the process to a second

or third person in the non-responding church if additional contact information was available. The

first point of contact was the executive pastor or equivalent, if an email address could be obtained, and

the second contact, if needed, was the senior pastor or his/her assistant, if an email address could be

obtained.

The 2015 survey effort included an additional 158 congregations between 500 and 1,800 weekly attenders

in size. This sample of Protestant churches suspected to have weekly worship attendances of

1,000 and higher was drawn from Leadership Network’s database augmented by specific denominational

records. These findings will be covered in a separate report at www.hartfordinstitute.org and later the two

size groupings will be compared and contrasted in a separate report. All figures used, unless otherwise noted, are self-reported from the churches. They were not independently

corroborated. The various tables and graphics may not total 100% due to rounding.

5 All averages in this report are medians, not means, unless noted.

6 All comparison research for smaller churches is 2015 data from a parallel survey sponsored by Faith Communities Today (FACT), a series of ongoing research surveys and practical reports about congregational

life, conducted and published by the Cooperative Congregations Studies Partnership, a multi-faith group

of 35 religious researchers and faith leaders. The research partnership includes members from more

than different faith groups, working in conjunction with Hartford Institute for Religion Research, Hartford

Seminary. FACT’s first national benchmark study was issued in 2000. Reports since then include national

studies in 2005, 2008 and 2010. The latest research from 2015 is currently being analyzed and will be

released in themed reports throughout 2015 and 2016 at www.faithcommunitiestoday.org.

7 American Community Survey: 2009-2013

http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-219.html.

Note: Leadership Network and Hartford Institute conducted this research without any input from The Beck Group. Upon seeing

the work, The Beck Group agreed it should be shared widely and joined the project to help see that happen.

All opinions expressed are from Leadership Network and Hartford Institute, not the sponsor. Our research has

its own biases but were not influenced by The Beck Group.

Further Reading

For full survey results of this and several megachurch research projects, go to www.hartfordinstitute.org/megachurch/megachurches_research.html.

For other reports our two organizations have co-authored visit our resources at Leadership Network www.leadnet.org/megachurch or Hartford Institute for Religion Research www.hartfordinstitute.org/megachurch/megachurches.html

This report was released on December 2, 2015. Copyright 2015 by Leadership Network and Hartford Seminary. We encourage you to use and share this material freely—but please don’t charge money for it, change the wording, or remove the copyright information.

If you have questions, please direct them to:

Scott Thumma

Hartford Institute for Religion Research

Hartford Seminary

77 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

sthumma@hartsem.edu |

Warren Bird

Leadership Network

2626 Cole Ave., Suite 900

Dallas, TX 75204

warren.bird@leadnet.org |

|